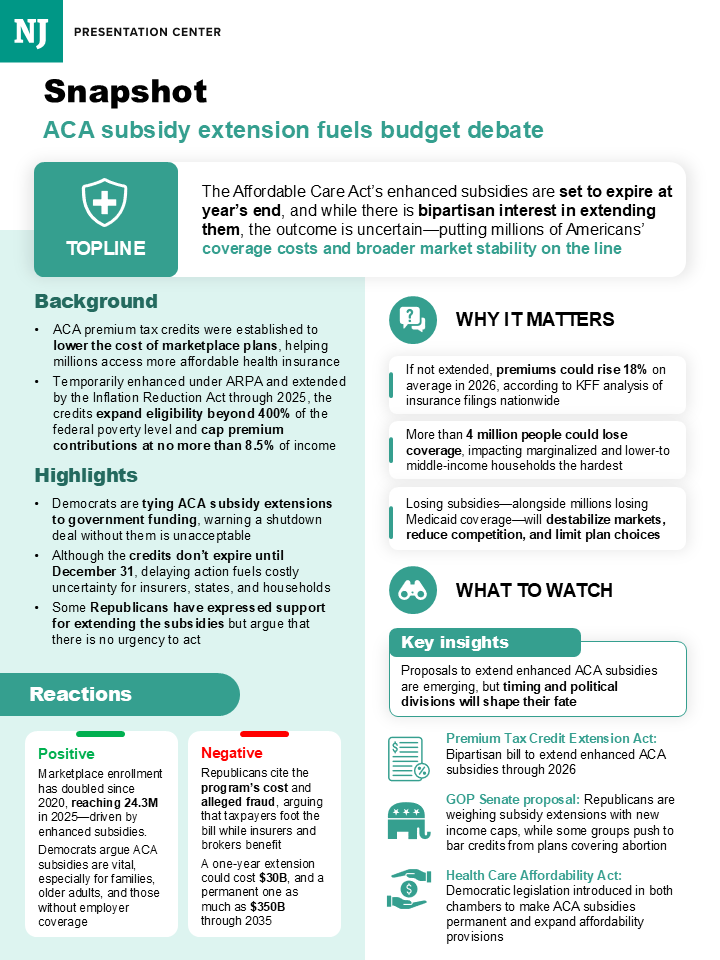

The Affordable Care Act’s enhanced premium tax credits are set to expire at the end of the year, but that doesn’t mean the negotiations to extend them are done.

Lawmakers are pushing talks to the beginning of next year—hoping to salvage the subsidies as health care and affordability have emerged as the themes likely to dominate next year’s elections.

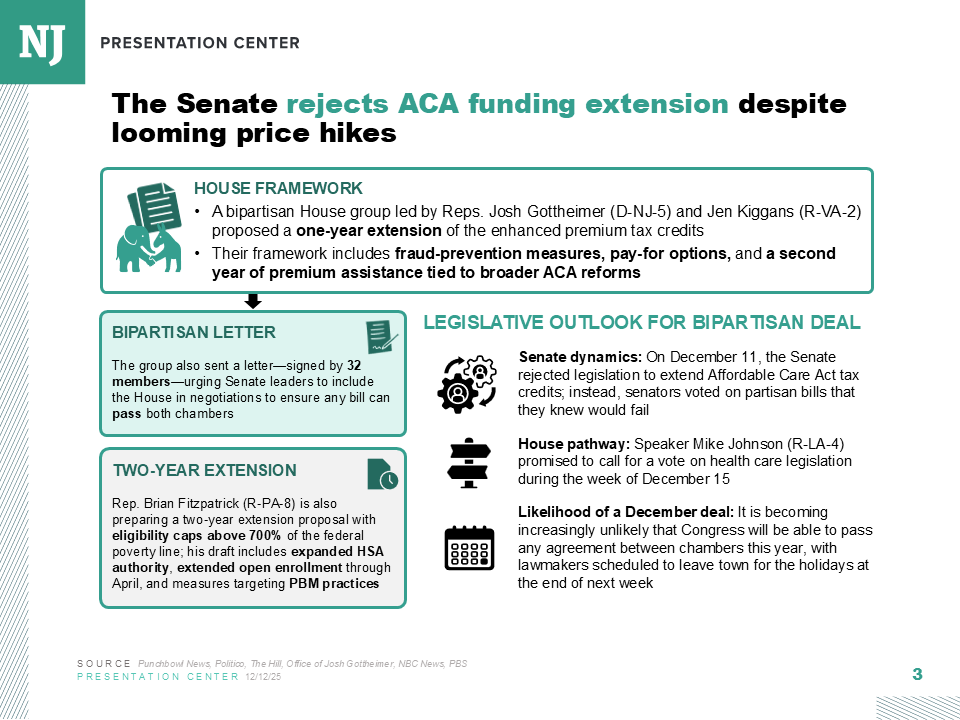

Congress left town last week without any clear resolution in sight on an extension of the enhanced Obamacare subsidies, which aid enrollees with the cost of premiums in the Affordable Care Act marketplace.

Centrist House Republicans have been struggling to corral the rest of their party to get on board with supporting an extension, fearing skyrocketing health care costs could cost the GOP at the ballot box next year. Those moderates escalated the battle by signing onto a Democratic-led procedural maneuver dubbed a discharge petition that would force a vote on the clean three-year extension of the enhanced subsidies when Congress returns in January.

While the House is expected to pass the extension, it’ll be up to the Senate to negotiate a deal and pull it over the finish line. Lawmakers in the lower chamber are expected to use the discharge petition to transmit a measure to the Senate—and any deal that’s decided would ride on that measure.

“We’re going to send them a vehicle, and that’ll be their decision as to what they can get,” said Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick, one of the moderate Republicans who broke ranks and signed onto the Democratic-led discharge petition. Discharge petitions compel a floor vote on measures if they reach the requisite 218 signatures.

After negotiations had floundered in the Senate, resulting in failed party-line voting exercises, much of the focus shifted to the House to see whether a compromise could be reached there. However, internal disagreements within the GOP over whether to grant an extension of the subsidies at all prompted many members to file discharge petitions on varied proposals that would extend the subsidies and enact reforms to the tax credits and the larger marketplace.

Conversations between House GOP moderates and their party’s leadership were focused on getting a floor vote on their proposals. Negotiations over an amendment vote to an alternative GOP health care plan introduced by leadership—one that did not include an extension of ACA subsidies—had collapsed last week, prompting the moderate Republicans to sign onto the opposing party’s measure. The alternative health care package, the Lower Health Care Premiums for All Americans Act, narrowly passed the House but is expected to be DOA in the Senate.

During negotiations, leadership asserted that any amendment extending the subsidies would need to be paid for. Moderates took issue with that condition, arguing that the party’s “One Big Beautiful Bill” Act passed this summer had included a budgeting gimmick dubbed the “current-policy baseline” that masked the projected trillions the measure will add to the national debt due to its significant tax cuts. Moderates argued that it was hypocritical not to consider the ACA subsidy measure under the same budgeting baseline.

“There will be consequences if these amendments are not made in order,” Fitzpatrick said.

Shortly afterward, the House Rules Committee ruled the amendments out of order and dismissed consideration of the provisions, prompting four House Republicans to sign onto the discharge petition filed by Democratic leader Hakeem Jeffries. The defection of those four Republicans—Reps. Fitzpatrick, Mike Lawler, Rob Bresnahan, and Ryan Mackenzie—meant the petition could move forward.

With a floor vote set to happen sometime in January, the measure is all but certain to be changed if rank-and-file lawmakers can reach a deal. That’s because the GOP-controlled Senate already rejected the exact proposal in Jeffries’ petition.

Privately, some House Democrats are giving their blessing for the Senate to do what they can, before momentum on the issue dies and election-year politics begin to influence the outcome.

“I think what we want is to make sure that people get more affordable health care and get their premiums down—and how we get there is less important than getting there,” said one House Democrat involved in conversations with Republicans. “We've all been kind of agnostic about which vehicle. With a one-year, two-, or three-year [extension], I'm actually totally agnostic.”

Senators have already started to coalesce around a specific proposal introduced by GOP Sens. Susan Collins and Bernie Moreno. While legislative text has yet to be introduced, their framework would provide a two-year extension of the enhanced tax credits, enact an income cap for those with household incomes of $200,000, and end zero-dollar premiums by requiring a $25 minimum monthly premium payment as a way to address fraud within the marketplaces.

In a gaggle with reporters last Wednesday, Moreno mentioned that lawmakers also plan on extending the open-enrollment period through February—giving constituents a chance to re-enroll, especially if they opted out of coverage due to the sticker shock from higher premiums.

“The concept of income caps, fraud prevention, and then giving people options in the second year is something that we’re still in discussions about,” Moreno said.

Some members of Senate Democratic leadership sounded warm to the proposal. However, a few Republican senators remain skeptical about a deal coming together—especially after negotiations collapsed over GOP demands to include the Hyde Amendment, which bans the use of federal funds for most abortions, a concession Democrats have made clear they won’t accept.

Sen. Mike Rounds, one of the key Republican negotiators, told National Journal he’s pessimistic about getting any deal done by the end of January because it likely hinges on “addressing the issue of the Hyde Amendment.”

The South Dakota Republican also said the Collins-Moreno proposal “needs some work.”

“It’s good that they’re working, trying to find a common approach, but it’s not done yet,” Rounds said.

As of now, the talks continue and a deal at least remains a possibility.

“I think that the discussions are continuing to occur between members on the Republican side and the Democrat side on the path forward,” Senate Majority Leader John Thune said. “We’ll see if there’s a landing spot. … If they send something over, it creates a revenue vehicle that we could use for something.”

There’s another wrinkle: The enactment of the Collins-Moreno proposal could prove difficult for insurers and state regulators that oversee the marketplace. While a clean extension would be relatively straightforward and easily applied, enacting the reforms on who and how enrollees qualify would be difficult, experts told National Journal.

“Any changes to the enhanced tax credits would certainly complicate matters for ACA marketplaces,” said Larry Levitt, the executive vice president of health policy for KFF, a nonpartisan health-policy research organization. “An income limit, a minimum premium, would take more time for marketplaces to program and certainly complicate the outreach to consumers.”

While senators say they are optimistic the reforms they’re proposing would be enacted in the 2026 year, it’s unclear how long it would take for these changes to kick in. And if open enrollment were to be extended to the end of February, it would leave little time for marketplaces to implement those changes and educate consumers and potential enrollees, according to Levitt.

Also, while the extension of the subsidies would provide relief to those purchasing premiums, that doesn’t mean that premium rates would change—which means the premium spikes that enrollees saw during this past enrollment period, at an average of 26 percent on the ACA marketplace, are here to stay. Without an extension of the subsidy, KFF estimates that enrollees who previously had their premiums subsidized will see their monthly payments more than double, increasing by roughly 114 percent on average.

“With each passing day that the enhanced tax credits are not extended, there is a certain amount of damage done, with people going uninsured because of the cost increases,” Levitt said.