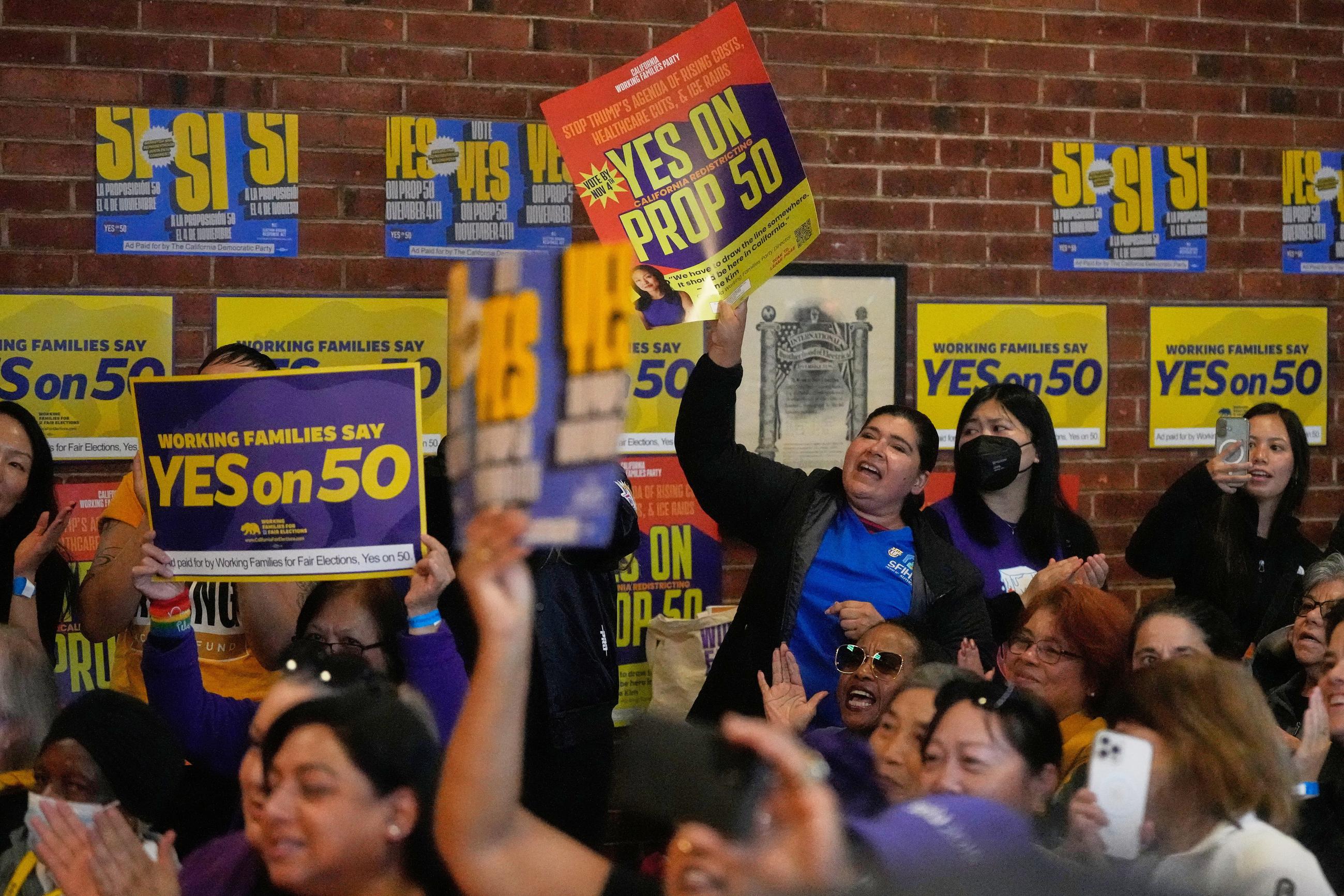

A midterm election cycle that started out like any other was upended this summer when President Trump called on Texas to revisit its congressional lines to net a handful of GOP seats.

That kicked off a rapid race across the country to change district lines in the middle of the decade in an attempt to gain a partisan advantage in a narrowly divided Congress. More than 10 states may have new lines by the time the dust settles.

Mid-cycle redistricting is not an uncommon phenomenon in politics—there have not been consecutive elections with the same nationwide congressional map since 2014, according to John Bisognano, president of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee. But such changes were relatively minor and often came in the form of court-mandated redistricting.

The effects of the current rampant, unprecedented, partisan mid-decade redraws will have ramifications well beyond the midterms.

“This is not good for states. This is not good for governance,” said Abha Khanna, an attorney at left-leaning law firm Elias Law Group, which is involved in a spate of redistricting cases throughout the country. “All this is a constant chasing of power and nothing else. It’s not what democracy was intended to do, and it’s not what government is intended to do.”

Elias Law filed a lawsuit at the end of October challenging a Staten Island district in New York. If successful, it could net Democrats an extra seat.

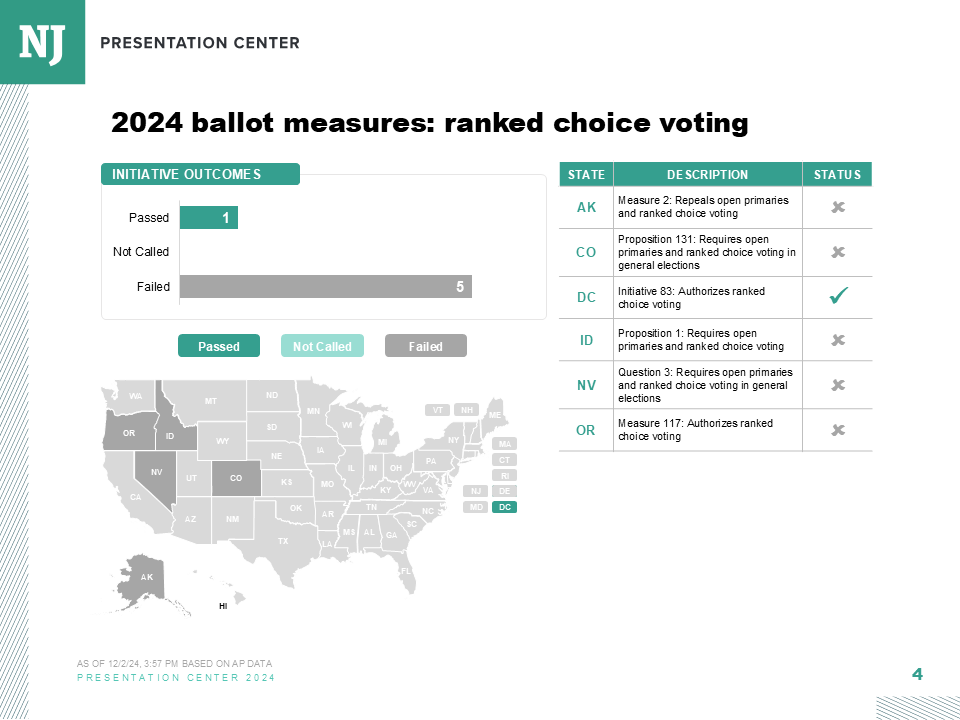

At present, there does not seem to be an end in sight for this arms race. But it remains to be seen whether this will become the new norm. A few members of Congress who have been affected have introduced legislation to ban mid-decade redistricting, but it’s unlikely the bills will gain much traction at the federal level.

On the other hand, some states, like New York, have begun to look at undoing independent commissions via constitutional amendment to restore map-making power back to state legislatures.

Some remain hopeful this redistricting arms race ends in disarmament.

“I still believe that this ends with national reform, and that being federal legislation to curb political gerrymandering in some capacity,” Bisognano said. “I think that’s the only way to end this current spiral that is being forced upon this country.”

Supreme Court intervention is unlikely, at least as it’s currently constituted. The John Roberts-led Court in 2019 ruled that partisan-gerrymandering claims were beyond the high court’s purview, instead kicking it to the states and Congress to curb such matters.

Republicans agree the solution must come from Congress.

“When you get into a nuclear arms race, it takes some pretty big cojones to get out of it,” said Mark Meuser, a California-based Republican election lawyer. “At some point in time it’s going to take some politicians who are willing to become statesmen and say, ‘Congress, we’ve got to step up and do the right thing.’”

Even if partisans eventually lay down their redistricting arms, a potentially more impactful specter haunts long-term map-drawing processes. The Supreme Court last month reheard arguments in a racial-gerrymandering case concerning the congressional map in Louisiana.

The justices asked parties to answer whether race-based districts violate the Constitution, a signal to some observers that the Court could be gearing up to gut Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which protects minority voting power.

Predicting how the Court might rule is a fool’s errand, said Justin Levitt, a former Obama and Biden administration official for voting rights, and it’s no guarantee they will strike down the law.

“I see parallels to the Alabama case two years ago, where the signals all looked like the Supreme Court was getting ready to strike down the Voting Rights Act, and then they turned around and said, ‘Nope,’” Levitt said.

The original hearing dissected the tension between race and politics, which are particularly intertwined in the South. Levitt said there’s a possibility of a narrow ruling only tailored to the Louisiana map.

“It just doesn’t seem to be where they’re leaning,” he added.

States across the South are readying for the possibility of the end of the Voting Rights Act. Worried Democratic groups warn that as many as 19 seats could be gutted. Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry, who was influential in enacting the current lines, called a special session to push back the state’s primary date in case the Supreme Court drops its decision before the end of the year, while South Carolina gubernatorial contenders are advocating to dismantle the lone Black-majority seat in the state.

Most experts agree any landmark ruling won’t affect the 2026 midterms, as the process to craft an opinion is often long and new districts would take time to implement.

But, should the ruling come, likely toward the end of the term in June, it promises to significantly shape how districts are drawn after 2030 and beyond.

Elias Law Group’s Khanna, who said she is optimistic the Court will uphold the Voting Rights Act, stressed the importance of the case.

“Anytime that the Supreme Court decides to opine on the Voting Rights Act, which is one of the seminal pieces of civil rights legislation in our history, it is consequential," she said.

“And we should all stand up and take notice.”