ALONG THE RIO GRANDE VALLEY, Texas—Tucked away in the southeast corner of Texas, the Lower Rio Grande Valley is, in many respects, the epicenter of political shifts in the United States. The fast-growing region, anchored by Hidalgo County, has surpassed El Paso as Texas’s largest metropolitan area along the border.

The area is staunchly working-class. Small businesses—and their struggles in an uncertain economy—predominate. Faith plays a big role in people’s lives. The census doesn't ask for religious affiliation, but it’s fair to assume the majority of residents are or were raised Catholic. The region quickly turns rural outside city limits, and residents in some places have to drive long distances to reach necessities like health care. For some, it’s cheaper and easier to cross the border to receive medical attention in Mexico.

Hillary Clinton won the region convincingly in 2016, but since then it has seen steady shifts toward the Republican Party, culminating in 2022, when Republicans won congressional seats here for the first time ever. Former Rep. Mayra Flores became the first Republican to represent the region when she flipped a seat in a special election for the 34th Congressional District. A few months later, Rep. Monica De La Cruz became the first Republican to win in the 15th District.

Flores would lose that same election, as the lines shifted to a more Democratic-leaning district following reapportionment. But the gains for her party were emblematic of political changes in what was traditionally a Democratic stronghold. In 2024, Hispanic voters turned out in historic numbers for President Trump.

Now, emboldened by yet another new congressional map blessed by Trump, Republicans hope to flip the entire valley red. Yet those ambitions rely on continued drift by Hispanic voters toward the GOP.

The Texas redistricting plan revamps five congressional districts across the state, turning three formerly Democratic districts into Republican strongholds or Republican-leaning seats. The map also makes two border districts—already competitive—slightly redder.

The resulting map not only creates confusion for voters and candidates—who don’t necessarily know where they’ll run, amid a federal trial challenging the lines—but it also banks on the staying power of the Republican Party with Hispanic voters. The data used by Republicans during the redistricting process suggest they’re relying on these voters sticking with them, even as opinion polls show Hispanic voters nationwide souring on the president.

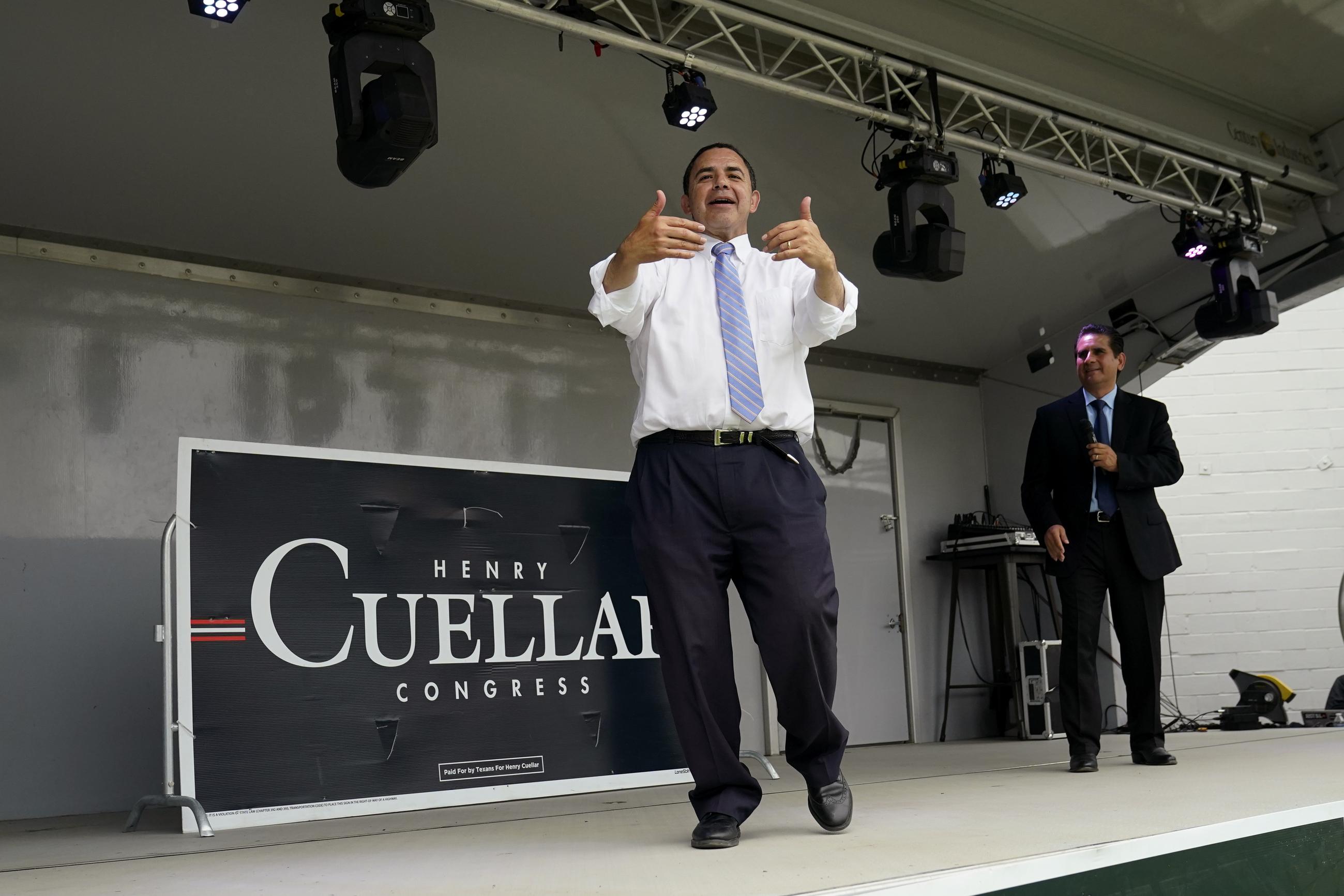

Democratic Rep. Henry Cuellar, who represents one of the South Texas districts facing changes, says he is not deterred by the new lines. In an interview with National Journal from his hometown of Laredo, Cuellar argued that he stands to benefit from the redistricting. He said the Texas Legislature based the new lines on Trump’s 2024 performance in the region, but they may not be able to reach that level again.

“I got 90-95 percent of the area that I currently represent or used to represent two-and-half years ago,” said Cuellar, referring to the 2021 post-apportionment map, which Texas recently modified.

Cuellar admitted that “three of [the districts] look tough for Democrats,” but the revisions are largely based on Trump’s performance in the region, and he believes downballot Democrats remained competitive in 2024.

Democrat Colin Allred would have narrowly lost Cuellar’s new district during his 2024 Senate campaign, while Beto O’Rourke would have carried the seat in his campaign for governor in 2022.

“It creates confusion more than anything,” Ada Cuellar, a Democrat running for Texas’s 15th Congressional District (and no relation to Henry), told National Journal from a diner in Weslaco, Texas.

Under the new lines, Weslaco sits in the 15th District, but if the map is struck down by the courts and Texas returns to its current lines, the city remains in the 34th District, held by Democratic Rep. Vicente Gonzalez.

Small details like this add to the confusion brought on by the sudden map changes, but Ada Cuellar said her strategy remains largely the same.

“We’re working on whatever map is the current map,” she said.

Voters don’t seem to have enjoyed the redistricting process. Allred is running for Senate again, and on campaign stops in Brownsville, McAllen, and Edinburg in early October, when he proclaimed his desire to ban gerrymandering nationwide, he was frequently met with a raucous applause.

“I hated it. Period. Flat out,” said Linda Yzaguirre, a student at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. “I hate this idea of uncertainty behind our politics and behind the people that get to choose who wins.”

Yzaguirre, a social-work student who has worked with some local agencies, says she worries about the needs of the community that could result from the gerrymandered maps.

“A lot of agencies will struggle. They will falter. … They all rely on the government to be able help fund and support people here,” she said.

For now, the new Texas map hangs in limbo, pending a ruling in a federal lawsuit. Arguments took place in El Paso in October.

The plaintiffs contend that racial considerations predominated in the drawing of the map. They point to a Justice Department letter sent to Gov. Greg Abbott outlining a handful of coalition districts—those in which multiple minority groups make up a majority—that needed to be rectified. Coalition districts are not protected by Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

Adam Kincaid, president of the National Republican Redistricting Trust and chief architect of the Texas map, testified that he did not consider race but only used political data.

A ruling is expected in time for the 2026 elections.

The region figures to be a central part of the battle for the House majority in the midterms, even if the map does not pass muster in court. Republicans signaled they would target Gonzalez’s seat in the Rio Grande Valley, as well as Cuellar’s district farther up the road in Laredo.

Democrats hope to find opportunity in the Republican-leaning 15th District, where Ada Cuellar and Tejano-music star Bobby Pulido are vying for the nomination.

Alvaro Corral, a professor of political science at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, says he doesn’t think it’s a “miscalculation to think voters will stick” with the Republican Party, “at least for the time being.”

The areas along the border have received significant attention as immigration has become a political wedge, particularly in the Trump administration. But the Rio Grande doesn’t feel like it’s under a microscope.

And yet, it just might be the most important political battlefield in 2026 and beyond to test the durability of the GOP’s new coalition.