Both on the campaign trail and since taking office, President Trump has promised that under his charge the U.S. will lead the world in artificial intelligence and return tens of thousands of advanced high-tech manufacturing jobs to the nation.

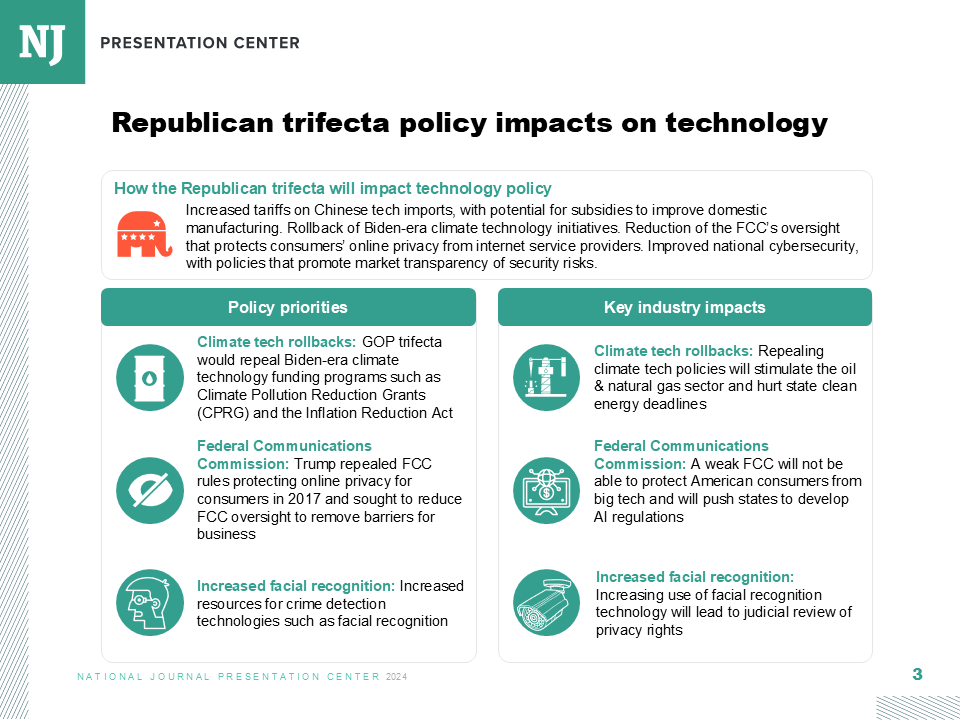

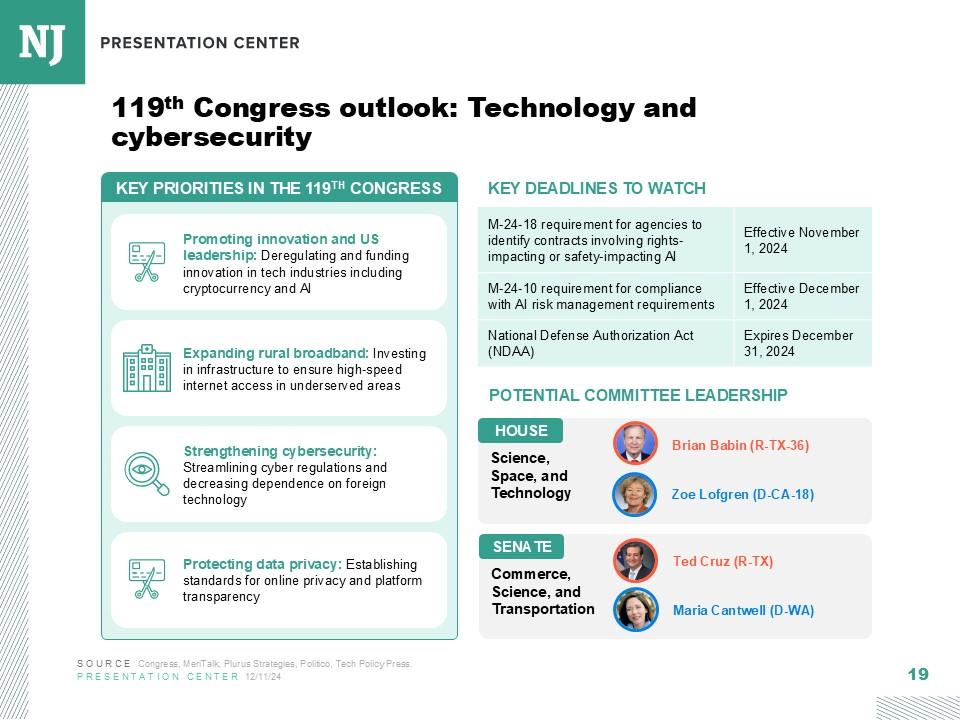

To achieve these lofty goals, the administration has accelerated the adoption of AI within the executive branch, peeled back some regulations put in place by the Biden administration, endorsed a hands-off regulatory strategy for AI, bought a 10 percent share in the tech giant Intel, and loosened semiconductor-export restrictions.

But experts have warned the administration’s hostility towards immigrants will act as a major roadblock to their tech goals—and an update to the H-1B visa program that will make it more expensive for American firms and universities to hire skilled foreign workers might be the latest setback for the tech world.

“We’re seeing another example of mixed motives,” said Mark Muro, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “There’s no doubt this could be extremely disruptive to the U.S. innovation and tech system.”

The change requires companies applying for an H-1B visa to pay a $100,000 fee before their application can even be considered, with an exception for workers who are already in the U.S. on another visa. Trump announced the program during a White House event where he also unveiled a $1 million “gold card” visa for wealthy individuals.

The current program has a cap of 65,000 workers, with an additional 20,000 slots for immigrant workers with advanced degrees. Universities, nonprofits, and government research organizations are exempted from the cap. When there are more applicants than slots available, as has been the case every year since 2014, recipients are chosen by a random lottery.

While the H-1B visa was designed to bring in the most skilled and knowledgeable workers from around the world for every industry, the tech industry has become by far its primary user. In 2025, Amazon led the nation in H-1B visa usage—nearly double the second-place finisher—while Microsoft, Meta, Apple, and Google were all in the top six H-1B employers.

But H-1B visas aren’t just for tech giants; they’re a particular boon to businesses trying to get off the ground.

A 2021 study found that tech startups that employ a high number of H-1B visa recipients are more likely to receive venture capital cash and have successful outcomes than those that don’t. In the AI world, 60 percent of companies were founded or co-founded by immigrants, many of whom—including Elon Musk—were H-1B visa recipients at one point in time. And 70 percent of full-time graduate students in AI-related fields are immigrants and potential future H-1B visa recipients, a 2022 study from the National Foundation for American Policy found.

“When we have H-1B workers, we bring in more patents, we bring in more more startup companies,” said Steven Hubbard, a data scientist at the American Immigration Council.

But Trump has been a long-time adversary of the program, which he and his allies claim tech companies abuse to drive down labor costs. During his first term, he used COVID as an excuse to temporarily freeze the program.

In his second term, one of the first internal battles between Trump and his advisers came when then-Trump allies Vivek Ramaswamy and Elon Musk forcefully defended the program just before Inauguration Day. While the two seemingly won the battle at first, Ramaswamy’s rant on H-1B visas reportedly helped lead to his DOGE ouster before the group really began its work, while Musk split with Trump over the summer.

In its recent announcement, the administration said the new fee would end abuses of the system, increase the number of tech jobs held by American citizens, and help protect national security.

“The severe harms that the large-scale abuse of this program has inflicted on our economic and national security demands an immediate response,” Trump said in the announcement.

Lora Ries, director of the conservative Heritage Foundation’s Border Security and Immigration Center, said the new fee is a good starting point for H-1B visa reform.

“Unfortunately, the H-1B program has gone far astray from the original intent, which was to supplement the American workforce where we are lacking,” she said. “This $100,000 fee is going to make employers have to prioritize who they really want to come on an H-1B instead of crashing the lottery and watering down standards, watering down wages.”

Research into whether the H-1B visa program actually lowers salaries for tech employees or pushes them out of jobs has been inconclusive. A 2021 study concluded every two H-1B visa recipients pushes three citizens out of a job, while a 2024 study found that each recipient actually created 0.83 jobs for citizens at that firm.

The H-1B visa program requires companies to pay their immigrant workers at least what they would have paid a citizen, with calculations based on the prevailing wage of a job in a geographic region, or based on what the company is already paying other employees with the same job title.

Both critics and supporters of the program say that companies have gamed the system. Some companies have tried to take advantage of the H-1B visa lottery by submitting hundreds if not thousands of applications, understanding that only about 20 percent will actually be accepted, according to critics. They then pay those workers relatively low salaries while contracting them out to tech companies with open spots.

The H-1B program is “a couple of different pipelines, wrapped up under the same umbrella," said Jeremy Neufeld, the director of immigration policy with the Institute for Progress. "You have the actual top superstar talent pipeline, where we’re getting Nobel Prize-winning scientists who are immigrants working at universities. On the other hand, you have these outsourcing companies which take up a lot of slots.”

Muro said that although he opposes the new fee, it might be helpful in reducing the number of H-1B visa recipients who are taking entry- and mid-level coding jobs at big tech firms that could reasonably be done by many U.S. workers.

Neufeld said outsourcing companies likely have the tools to avoid the new fee by bringing workers to the U.S. under a different visa that’s cheaper, then applying to transfer them to H-1B status without paying the $100,000 fee.

But he said the fee would be particularly devastating for research institutions, which are exempt from the cap.

“It’s going to be a huge blow for our international talent pipelines in scientific and academic research,” Neufeld said. Those institutions “are largely not going to be able to pay $100,000 for junior-level faculty or even an assistant professor who may end up making incredibly major contributions to their fields.”

Instead of a fee, he suggested the government should focus on changing the lottery system to target higher-paid, specialized roles that only a handful of people around the world could fill.

On Tuesday, the Trump administration proposed a new rule that would split H-1B visa jobs into four categories based on wage level. The change would allow companies to receive more lottery entries for higher-paying jobs than for lower-paying ones. Under the proposed rule, the highest-paying job would enter the lottery four times, while the lowest-paying jobs would be entered just once.

The proposed rule will go through a 30-day comment period before being considered for final adoption, a process that could take months. Both the fee and the proposed rule will also likely face court challenges, delaying and possibly blocking implementation while adding uncertainty to the process.

“Congress has explained how fees are supposed to work. They’ve given some guardrails on what the purpose of the exclusion power is, so I don’t think [the new fee is] likely to hold up in court,” Neufeld said. “The long shot of all of this: There's going to be a huge legal battle, [it] probably will get struck down in the end, and the whole time, it’s just a big signal of uncertainty to people we should be trying desperately to recruit, because they’re such assets in the country.”