Just as the IRS is facing a historic reduction in workforce, Congress has handed the nation’s tax collector a massive new bill to process. Whether the agency has the capacity to implement the changes to tax law in a timely manner remains unclear.

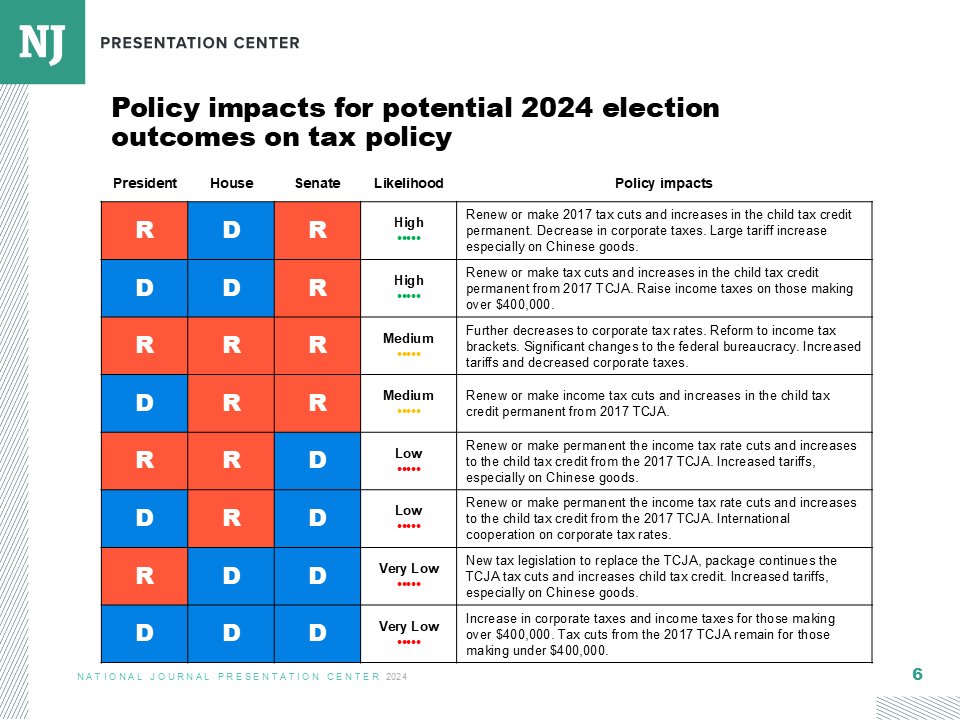

The “One Big Beautiful Bill” is the most sweeping piece of tax legislation since the 2017 tax code overhaul. It renews the 2017 tax breaks while also rolling out new provisions, such as deductions for tips and overtime, new tax-advantaged savings accounts, and a new system for taxing gambling winnings. Some of these provisions will go into effect as soon as the 2026 filing season, giving the agency only a few months to draft and implement new rules to administer the changes.

It’s a tall order, and one that analysts and former top-level leadership at the agency say could be made more difficult by the bone-deep cuts to the IRS workforce spearheaded by the Department of Government Efficiency, as well as cuts to agency funding proposed by lawmakers.

“The IRS is an agency that is used to doing more with less, but what they’ve been asked to do this year is unprecedented, and the consequences are something that the taxpayers will find out next year,” Vanessa Williamson, senior fellow of governance studies at the Brookings Institution, told National Journal.

This isn’t an unfamiliar position for the agency. Lawmakers slashed IRS funding for years in the run-up to the 2017 tax code overhaul, which experts warned would pose challenges for writing and rolling out new regulations.

The agency pulled through, and the next year’s filing season was a success by most accounts. The current measure isn’t as large in scope as the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, but the push to slash the agency’s workforce is more severe.

“The IRS, back when TCJA was passed, had more folks to help taxpayers who were trying to comply, and more personnel then to audit and compel taxpayers who were not paying their fair share to do so,” Larry Gibbs, who served as IRS commissioner during the Reagan administration, told National Journal. “They're gone. The numbers are now below the numbers that we had with TCJA.”

The Trump administration has cut more than 25 percent of IRS staff, including at least one-third of tax auditors, according to a May 2 report from the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, the agency’s watchdog.

“When the IRS was really in crisis in terms of providing service in the 2010s, they were losing 2 percent of their staff a year because they had a freeze. So we’re talking about 10 times that in a single year,” Williamson said. “We’re really operating outside of what has ever been experienced.”

Even if the administration reverses course and works to refill those empty positions, it will be a challenge, she added. “If you have job options, are you going to come to the place that fired a quarter of its staff this year?”

IRS funding is on the chopping block as well. The House’s fiscal 2026 Financial Services and General Government appropriations bill would reduce IRS funding by more than 20 percent from current levels, dropping from $12.3 billion to $9.5 billion. Most of the cuts would come from the agency’s tax-code enforcement arm. The measure has cleared its subcommittee, but the full panel has not yet held a markup ahead of the Sept. 30 deadline to fund the government.

Congress is also taking steps to claw back the agency’s cash infusion provided by the Biden-era Inflation Reduction Act, which initially provided $80 billion in additional funding through 2031 for IRS modernization and tax-code enforcement. Congressional Republicans have pushed to slash more than $20 billion of that funding in subsequent legislation.

So with reductions in funding and workforce, and while continuing to enforce the existing tax code, the agency must now take on the task of interpreting tax elements of the One Big Beautiful Bill. It must draft rules, collect public comments, and issue final regulations on the new provisions in time for the next filing season.

“They’ve got to get decisions made about what the guidance is going to be, they’re going to have to come up with interpretations before the filing season,” said Gibbs. “They’ve got to train the people that are going to be on the phones, the people that are going to assist taxpayers.”

Even taxpayers not directly affected by the changes could face obstacles when they file. New taxes or tax breaks often generate questions from the public, which places strain on the agency’s helpline. The agency’s Taxpayer Services division, which handles questions from the public, has lost 20 percent of its workforce since January, according to the National Taxpayer Advocate.

Williamson said new provisions like the deductions for tips and overtime could create increased demand on taxpayer services.

“A lot of taxpayers might want to understand whether this is a method that applies to them,” Williamson said, “and the IRS is going to be hard-pressed to respond.”

The administration is aware of the potential resource shortfall and has asked Congress for more money for the Taxpayer Services division, though cuts are still proposed elsewhere at the agency. Lawmakers have so far rebuffed the request. The IRS’s fiscal 2026 budget request said that, without a boost in funding, the agency could only answer 16 percent of calls in the new tax year, down from 85 percent in 2025.

“At this level of service, most taxpayers would be unable to reach the IRS by phone or receive answers to questions related to tax compliance,” the agency predicted. “Taxpayers that do get through would face long wait times.”

Gibbs noted that the current IRS commissioner, former Rep. Billy Long, has said he will push back the beginning of next year’s filing season by about a month, to around President’s Day in February. That’s a smart move, Gibbs said, given the mammoth task ahead of him.

Williamson noted a final concern, saying the public might not learn exactly how much customer service has declined at the IRS.

In June, the Washington Post reported that the Social Security Administration had quietly stopped posting customer service performance metrics such as call wait times on its website. If the same thing happens at the IRS, both the public and lawmakers overseeing the agency may not know how the agency’s taxpayer services are faring.

“I expect to see problems with wait times,” Williamson said. “I expect to see slower refunds. It’ll just be very hard to get clarity on how to file a tax return correctly if [people] have a question.”