Lujain Hamza, a Druze doctor based in the Syrian city of Sweida, has spent the past two weeks in terror.

Sweida is a predominantly Druze city in southern Syria, located near the border with Jordan. Since mid-July it has become the site of ethnic violence between government forces and the nation's Druze minority, who have experienced horrific atrocities. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a monitoring group, said more than 1,300 people were killed in clashes in recent weeks, with nearly 200 believed to have been executed.

Hamza said she believes the number could be much higher. Many of the people killed, she said, were murdered in their homes or while attempting to flee the city. A Christian pastor and members of his family were among those killed.

“It was random. Whenever they saw anything moving, they would kill them. They burned shops, they burned cars, they burned houses,” Hamza told National Journal in a phone call from Sweida on Thursday. “Whenever they couldn’t rob a house, they would burn it. A friend of mine and his wife were killed in their house, both of them, and then they cut his wife’s arm from the wrist down to steal her bracelet.”

Hamza said hundreds of people have been kidnapped, and members of the local Druze community found the naked corpses of 15 women and children on the outskirts of the city who had been raped and killed, their bodies thrown in the street. National Journal could not independently verify these claims.

On the first day of the fighting, Hamza said she started to hear explosions. She brought her mother to a friend’s house, and the two women hid there.

“It became crazy. We were so scared. It was raining bombs and rockets, raining on the city, on the civilians, in the middle of Sweida. We were expecting to be killed at any time. It was horrible. We couldn’t sleep for three days,” she said. “There were 19 of us—women with children—hiding in a small room in the middle of the house, because it was the safest room. But of course no place was safe in Sweida.”

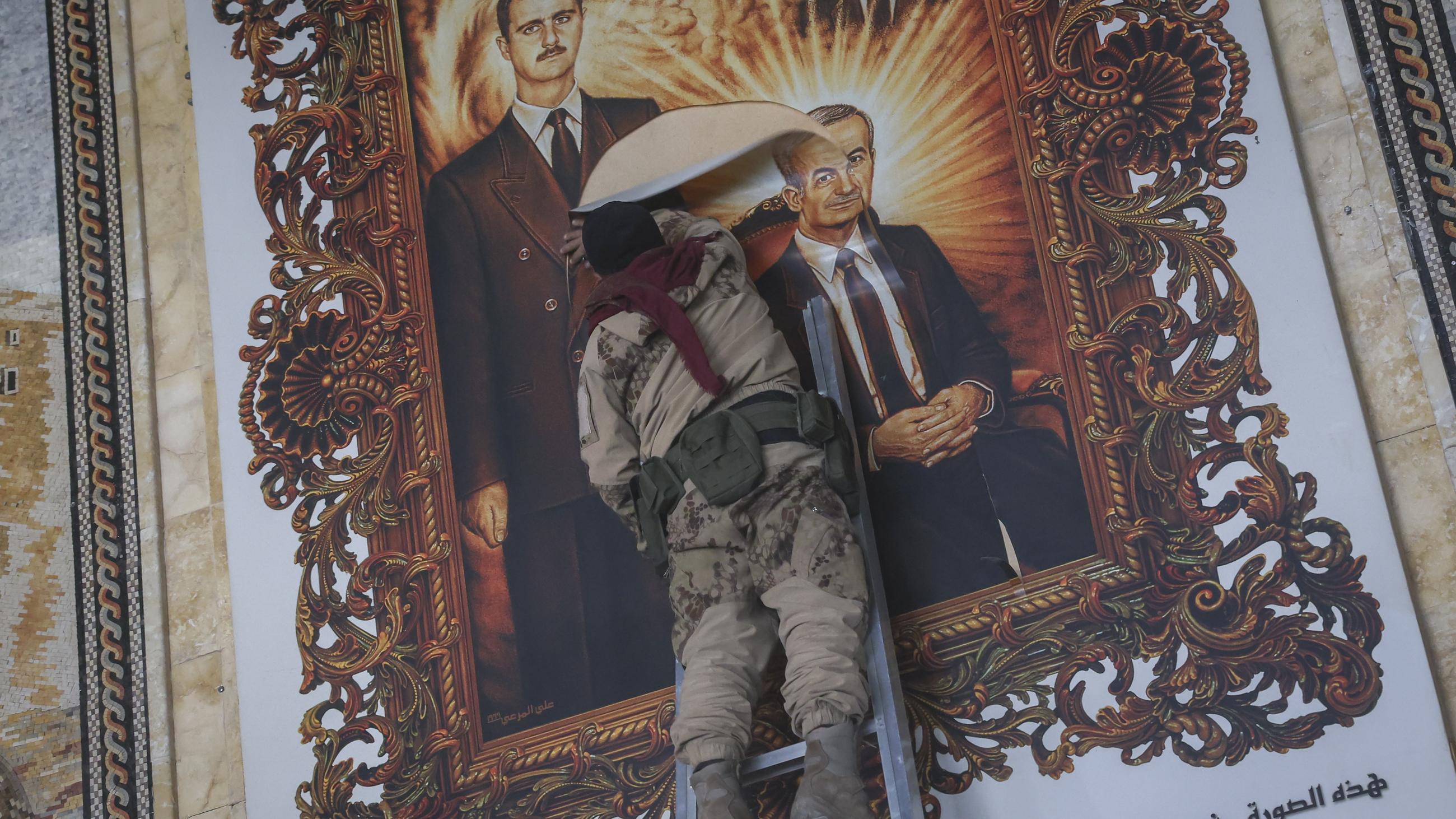

The attacks are occurring just months after longtime dictator Bashar al-Assad was forced to flee from the Syrian capital of Damascus, ending the 14-year Syrian civil war and allowing former rebel fighters to form a new interim government. But fighters linked to Syria’s security forces have allegedly carried out crimes that could throw the country’s future into chaos again.

Meanwhile, lifting sanctions on the government of the Syrian interim president, Ahmed al-Sharaa, the former leader of the rebel group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), has emerged as a rare point of bipartisan consensus in Washington and within the international community.

Many policy makers argue that it’s imperative to work with the new government in Damascus and lift restrictions on business if Syria is to have a chance at rebuilding after so many years of war.

In June, a bipartisan group of lawmakers in the House of Representatives introduced a bill to lift Assad-era sanctions on Syria. Separately, Reps. Ilhan Omar and Anna Paulina Luna unveiled the Syria Sanctions Relief Act to repeal existing sanctions.

“Syria’s remarkable transition, and the end of the decades-long Assad dictatorship, presents new opportunities for engagement for the betterment of the Syrian people. This is the right time to lift sanctions,” Omar said.

Later that month, Sens. James Risch and Jeanne Shaheen, the top Republican and Democrat on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, released a joint statement in support of President Trump’s executive order to lift some sanctions on the country. The organization Human Rights Watch said lifting sanctions on Syria would “bolster rights and recovery.”

But international support is contingent on HTS and its allies respecting the rights of Syria’s many ethnic and religious minorities. People like Hamza say they cannot trust the new government.

Sometime on July 13, clashes broke out between Bedouin tribesmen and the Druze community after a Druze man was allegedly attacked at a checkpoint. The incident reportedly triggered a cycle of retribution, and government security forces were dispatched to the area. What followed was a series of attacks that led to thousands of deaths, including extrajudicial executions.

The United Nations reported that since July 12, at least 93,400 people have been displaced, with the majority coming from Sweida. The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom condemned the attacks.

“This latest attack in [Sweida] is a clear indication that the transitional authorities are failing to rein in violent extremist groups and protect the diverse Syrian populations they claim to represent,” said USCIRF Commissioner Maureen Ferguson.

Israel eventually got involved, carrying out strikes on Sweida on July 17 that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said aimed to protect the Druze minority. Hamza said she was relieved that Israel got involved on behalf of her community. She believes those strikes saved her life and the lives of many other Druze.

“There was a military convoy coming into Sweida, coming from the Ministry of Defense. Its length was 35 kilometers (roughly 22 miles). There were more than 90 tanks and a lot of heavy weapons, coming to invade Sweida,” Hamza said. “This convoy was struck by Israel. So, we felt safe.”

Still, Hamza said she would like to see more action from the international community, including the opening of a border crossing with Jordan to facilitate a flow of goods and people.

“We want real help, direct help. Sanctions and these things aren’t helping anyone. They’re only making things worse,” Hamza told National Journal. “We want peacekeeping forces, scattered everywhere. We want a corridor to be opened between us and Jordan, because our only way to get food and fuel now is from Damascus. We have the right to have another border crossing. All the markets in Sweida, all the pharmacies, are empty. There is no equipment in the hospitals.”

The Syrian government and HTS-linked forces continue to control many of the villages surrounding Sweida. The U.N. has arrived to deliver basic foodstuffs to the population, and senior U.S., Syrian, and Israeli officials met Thursday to discuss ways to avoid an escalation of violence. U.S. Special Envoy for Syria Tom Barrack told Reuters that he warned al-Sharaa the government must be more inclusive toward minorities or risk losing international support.

In a televised speech, al-Sharaa said Israel was trying to destabilize Syria and insisted his “priority” was to protect Syria’s Druze. Hamza, however, said she doesn’t believe the new government in Damascus wants to protect minorities.

“They want to kill the minorities without anyone knowing that. They started from the coastline and then moved to Druze, and the whole time, they were killing Kurds. They are targeting minorities all over Syria,” Hamza said. “I don’t feel safe at all. Anyone now can kill you, just because you’re a minority.”