President Trump appears to have finally realized what most observers have known for years: Russian President Vladimir Putin doesn’t want to end the war in Ukraine.

Trump, who came to office promising to end the fighting on day one, has been pushing for months for Moscow and Kyiv to hammer out the terms of a ceasefire—but he has focused nearly all his attention on Ukraine.

He criticized Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky for failing to make concessions to Russia, which invaded its smaller neighbor in 2022, and refused to authorize new deliveries of much-needed military equipment to the besieged country. He also floated the idea of entering into lucrative business deals with Russia once the war ends, showing a willingness to pursue rapprochement with a country that has become a global pariah. Now, in a sudden U-turn in rhetoric, Trump finally seems to have figured out that Russia is the problem.

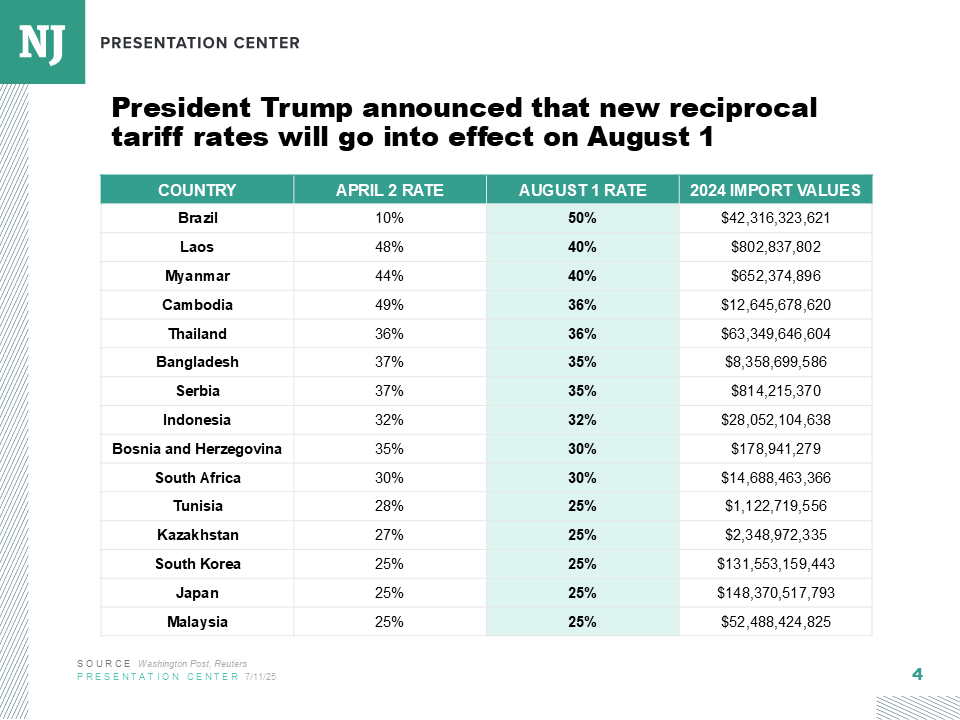

On Monday, he announced that Putin must end the war in 50 days or he would implement 100 percent tariffs on countries that continue to do business with Russia. Trump also agreed to sell more weapons to NATO member states with the understanding that the allies will pass them to Ukraine.

Many have interpreted Trump’s about-face as a significant victory for Kyiv, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte, and other allies of Ukraine who spent months trying to convince Trump that Russia is responsible for the war. During a visit to Congress on Tuesday, Rutte told reporters that the Trump administration will now supply weapons “massively” to Kyiv.

Nevertheless, Washington still hasn’t agreed to provide Ukraine with weapons from its own stockpiles. Instead, Trump has secured more of the foreign military sales he has long favored. Rutte, who has emerged as something of a Trump whisperer, stressed that Europe would pay for all the weapons Trump promised.

“Not just air defense. Also missiles. Also ammunition, paid for by the Europeans,” Rutte said. “We will find the money in Europe to make sure Ukraine has what it needs to be in the best possible position during these peace talks as soon as they start.”

Meanwhile, some are criticizing Trump’s decision to give Russia 50 days to end the war, arguing that it will provide Putin with more time to make battlefield gains.

“Fifty days is a very long time," the European Union’s foreign policy chief, Kaja Kallas, told reporters. That was echoed by U.S. foreign policy heavyweights such as Senate Foreign Relations Committee ranking member Jeanne Shaheen, who said that “every day Russia is able to continue this war means more havoc” in Ukraine. Sen. Thom Tillis, the Republican chair of the Senate’s NATO Observer Group, also said the 50-day delay “worries me,” because Putin will use it to try to win the war. In addition, Trump has shown a propensity to push back self-imposed deadlines, a pattern that has earned him the derisive moniker TACO (“Trump Always Chickens Out”).

Details about exactly which weapons packages NATO partners will send to Ukraine still need to be hammered out in closed-door negotiations, as some in the Pentagon express concern that U.S. stockpiles could be depleted. Those conversations will likely be spearheaded by the NATO Defense Contact Group, with U.S. Ambassador to NATO Matthew Whitaker taking a lead role.

However, the U.S. has committed to sending more Patriot missiles, which Ukraine desperately needs for air defense. In some cases, Washington’s European allies could send their own Patriot missiles to Ukraine and then purchase new ones from Washington later. In other cases, European allies might fund the direct delivery of U.S.-made missiles to Ukraine.

There are other signs Washington could renew its commitment to Ukraine.

European leaders representing the so-called Coalition of the Willing met in Paris last week to discuss plans for a multinational peacekeeping force that would deploy to Ukraine after the war ends. A U.S. delegation attended the meeting for the first time. Then, following the Paris gathering, Gen. Keith Kellogg, the official U.S. representative for Russia and Ukraine, arrived in Kyiv for a visit on Sunday. Both sides called Kellogg’s meetings constructive.

During a recent Association of Southeast Asian Nations meeting in Malaysia, Secretary of State Marco Rubio met with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi on the sidelines of the event and took the opportunity to discuss Beijing’s support for Russia.

Meanwhile, some members of Congress are still pushing for a Russia sanctions bill, spearheaded by Sens. Lindsey Graham and Richard Blumenthal, to be brought to the Senate floor in the coming weeks.

Senate leadership has said the bill, which has garnered over 80 co-sponsors—a solid filibuster-proof majority—could get a vote before the annual August recess. If passed, the bill would give Trump the authority to implement tariffs of up to 500 percent on any country that continues to purchase Russian energy products. That's much higher than the 100 percent tariffs Trump floated Monday. Lawmakers argue that passing the bill would send a stronger message than just the president’s actions alone.

“It’s stronger, broader, and potentially more effective than an executive order,” Blumenthal told National Journal. “It shows the unity between Congress and the president, which sends a powerful message to the whole world, and it insulates sanctions against any legal challenges which there may be to an executive order.”

Graham, the Republican co-sponsor, told National Journal that lawmakers are continuing to discuss the bill with the White House.

“The goal of the bill is to create some leverage, and I think the bill can be helpful to President Trump,” Graham said. “The goal of the bill is to get Putin to the table, and what President Trump did was adopt the theory of the bill, so I am very pleased.”

However, Anders Åslund, an economist and expert on Russia and Ukraine, said it’s unlikely the U.S. will implement 500 percent tariffs on major trading partners such as China and India, which are currently two of the largest purchasers of Russian energy supplies. Economists widely agree the economic fallout from imposing such hefty tariffs on these partners would devastate the U.S.

“There are two alternatives: it’s either watered down to something that makes sense or it’s not adopted,” Åslund said. “If it really now goes ahead, it will be a major complication on many fronts because this would really hurt the relationship with India and China to such an extent that it would be quite undesirable.”

Åslund argued the threat of tariffs is simply intended to give the impression Trump is getting tough on Moscow. If the U.S. president wanted to help Ukraine, Åslund argued, he could seize Russia’s frozen Central Bank assets and transfer that money to Kyiv. There was bipartisan support for such a move in Congress under the Biden administration.

Still, not everyone thinks Graham and Blumenthal’s bill would be impossible to implement.

Kurt Volker, a former U.S. ambassador to NATO and special representative for Ukraine negotiations during the first Trump administration, said the only way to stop Putin from continuing the war in Ukraine indefinitely is to exert more economic pressure on Moscow and provide a steady flow of weaponry to Ukraine. He argues that the bill currently being pushed in the Senate could do just that.

“It will give Trump a tool in his toolbox. He can use it if he chooses to,” Volker said. “And if it is actually implemented vigorously, that means you are dissuading others from working with Russia on oil and gas movements. Then it could actually have an impact. The key is to try to dry up the flow of money from oil and gas sales that goes into the Kremlin’s bank accounts. That could have a significant impact on their ability to keep going [with the war], because it’s going to stretch state finances overall.”

Some argue the international community can do little to change Russia’s behavior: the Kremlin has demonstrated its commitment to pursuing the war and its ability to adapt to sanctions and other punitive measures. Nevertheless, David Salvo, an expert on Russian affairs at the German Marshall Fund, said the current bill in Congress sends an important message.

“I think it’s great that there’s such bipartisan consensus on getting tough on Russia’s enablers. I think that’s a good message to send to the Kremlin,” Salvo said. “If it at least dries up that source of revenue for Russia, great, they’re at least effective in that regard.”