When the White House unhesitatingly responded to the killing of Alex Pretti in Minneapolis on Saturday by trying to persuade Americans they had not really seen an innocent man gunned down by federal agents, it was not the first time they had asked the country to ignore or reinterpret dramatic video. Amazingly, even though that was less than a week ago, it was not even the most recent time.

From the first hours of his first term right up to as recently as Tuesday this week, President Trump and his White House and top aides have consistently and brazenly challenged reality, as represented by video taken by both professional news organizations and amateurs armed only with their cell-phone cameras.

For the most part, they have gotten away with it. Trump easily has batted away fact-checkers and critics and pressed forward unimpeded.

But not this time. The video of Pretti’s killing was too immediate, too heinous, too violent, and just too much for people to accept the White House rush to brand the 37-year-old nurse who took care of veterans as a would-be assassin who was a threat to heavily armed Border Patrol agents.

Lulled by the ease with which they denied past videos, White House officials were unprepared for the backlash this time. Perhaps the most surprising thing about the official reaction is that a team that prides itself on a particular savvy in the use of social media was so unaware of how the world has changed via the ubiquity of cell-phone cameras.

Before the explosion in smartphones, there was a dreary sameness to the aftermath of all police shootings. Officers defended their actions, usually saying they were forced to shoot to defend their own lives, even when witnesses and victims offered competing stories.

But this “he-said/they-said” changed with the advent of omnipresent video cameras. Nicol Turner Lee, director of the Center for Technology Innovation and senior fellow in governance studies at the Brookings Institution, dates the change to 2009 when Oscar Grant of Oakland was fatally shot by a BART police officer. It was the first police shooting of its kind captured by cell-phone cameras and uploaded to YouTube.

The vast majority of Americans—98 percent—now own a cell phone, according to Pew Research Center data. Almost as many—91 percent—own a smartphone with a camera, up from 35 percent in 2011.

Trump himself recoiled in 2020 when he watched video of the death of George Floyd after Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin knelt on his neck for almost eight minutes even while Floyd pleaded, “I can’t breathe.” Trump told Fox News, “Nothing has to be said. I watched that. I couldn’t really watch it for that long a period of time; it was over eight minutes. Who could watch that?” He told Sean Hannity that Chauvin “has some big problems,” adding of the video, “It doesn’t get any more obvious, or it doesn’t get any worse than that.”

For many in Trump’s orbit, that history competes against an impulse to play offense and attack those with competing narratives. The president gave voice to this mind-set in 2018, when he told the Veterans of Foreign Wars, “What you’re seeing and what you’re reading is not what’s happening.”

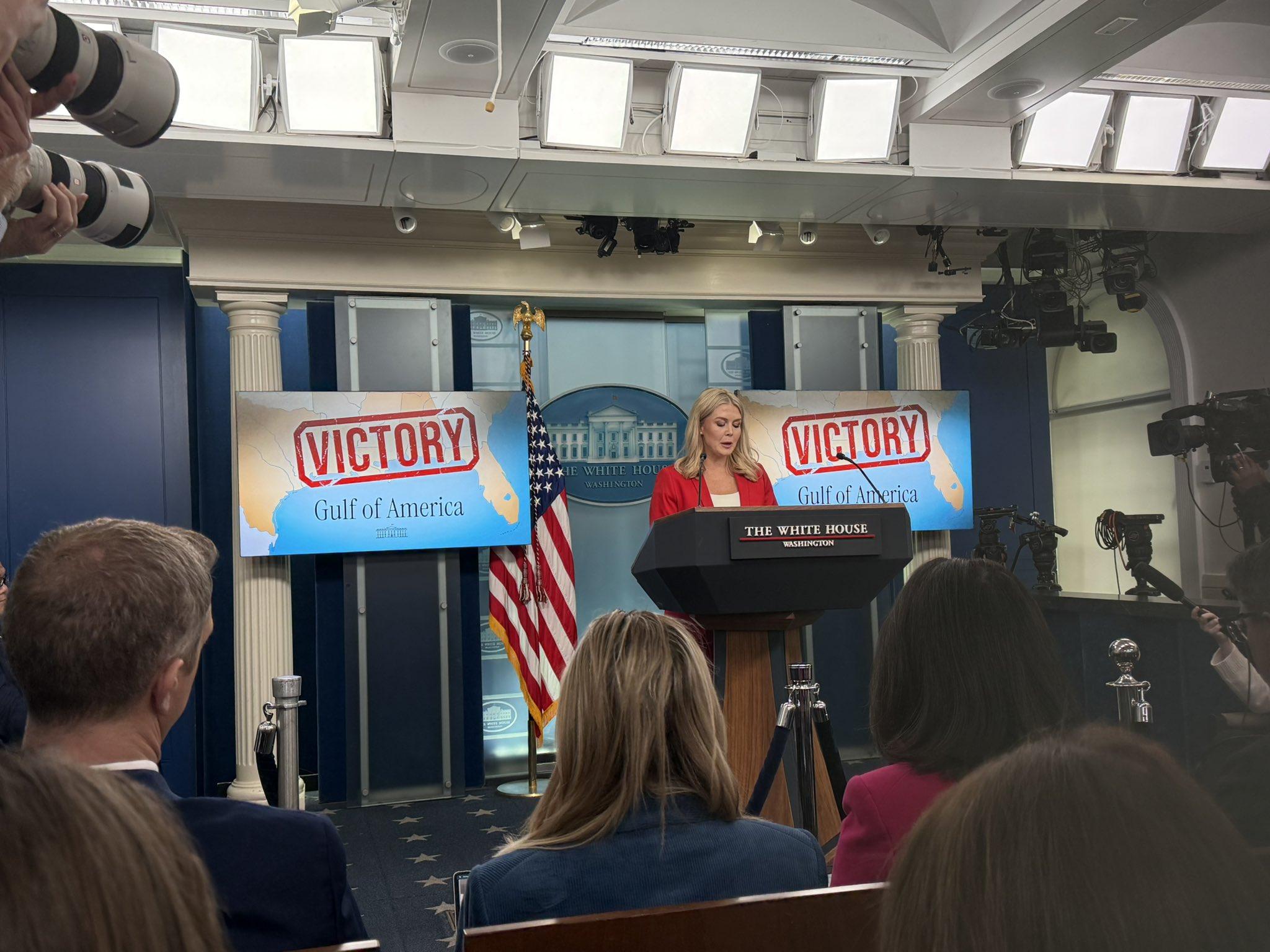

With the backlash to the administration’s initial reaction to the Pretti killing, the White House was thrown off stride. But it has not lost its certitude. Even as press secretary Karoline Leavitt was doing damage control in her briefing on Monday, the White House YouTube channel broadcast of the briefing included a banner: “Text ‘TRUTH’ to 45470 for updates from the White House.”

Here are seven examples of Trump's battles between his own “truth” and video evidence:

The voice on the Access Hollywood tape

As a candidate in 2016, Trump apologized for what he was heard saying on the Access Hollywood tape, calling it “locker-room talk.” But by the time he was president, he backtracked, calling for an “investigation" of the recording and telling a senator, “We don’t think that was my voice.” But the audio evidence left no doubt.

Iceland vs. Greenland

Only three days before Sunday’s Minneapolis shooting, the world listened to the president speak in Davos and heard him four times say “Iceland” when he meant “Greenland.” When a reporter noted what everybody had heard, the White House attacked. "No, he didn’t," Leavitt tweeted to the reporter. “His written remarks referred to Greenland as a ‘piece of ice’ because that’s what it is. You’re the only one mixing anything up here.”

The “largest” inaugural crowd

Trump had been president less than three hours in 2017 when he objected to reporters noting that his inaugural crowd was much smaller than Barack Obama’s in 2009. He ordered press secretary Sean Spicer to claim it “was the largest audience to ever witness an inauguration, period.” Trump then had a government photographer edit the official pictures to make the crowd appear bigger, according to documents that were later released.

The lawyer who wasn’t crying

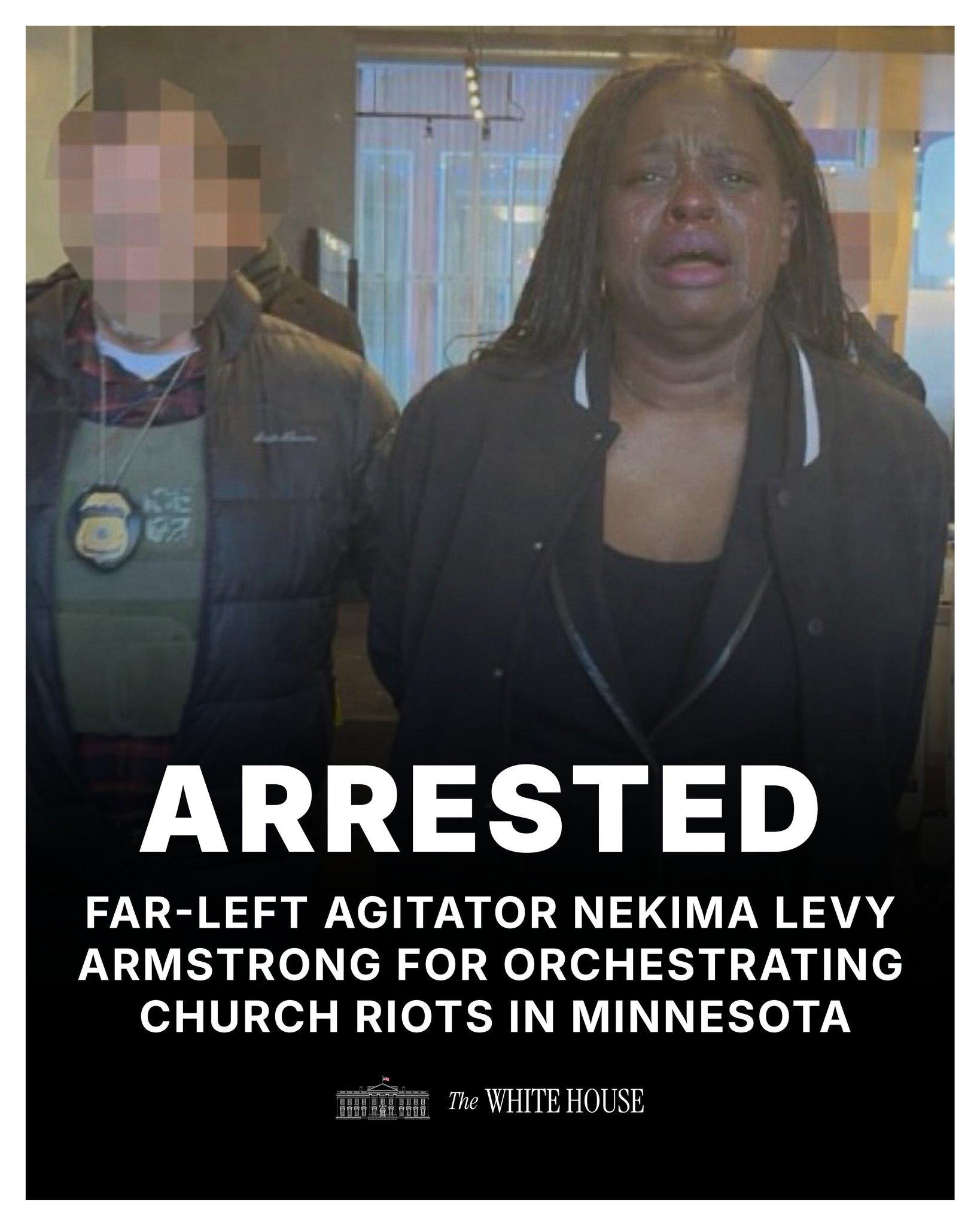

Last Thursday, civil rights attorney Nekima Levy Armstrong was arrested with two others for a protest that disrupted a service at a church whose pastor is an Immigration and Customs Enforcement official. Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem posted a picture on X of the arrest. Thirty minutes later, the White House tweeted out the same picture—with one notable difference. The White House had digitally altered the photo to show the lawyer weeping. When reporters noted the distortion, White House spokeswoman Abigail Jackson mocked them with her own X post: “uM, eXCuSe mE??? iS tHAt DiGiTAlLy AlTeReD?!?!?!?!?!”

“A day of love”

Few Americans avoided video of the violent scenes from the pro-Trump assault on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. But by 2024, now-candidate Trump asked them to forget the violence and see something that wasn’t evident in the video. During a Univision town hall shortly before Election Day, Trump contended, “That was a day of love.”

“I didn’t say that”

On Dec. 3, Trump was asked if he would authorize public release of video of the follow-up attack on a suspected drug-smuggling boat in the Caribbean in September. He responded, “Whatever they have we’d certainly release, no problem.” But when ABC’s Rachel Scott reminded him of that three days later, the president bristled. “I didn’t say that. That’s—you said that. I didn’t say that. This is ABC fake news.”

The gloved hand

The White House was back at it Tuesday, denying video evidence just three days after it should have learned the folly of doing that in Minneapolis. The stakes were not as high, but the video evidence was just as clear. It was sparked by MS NOW White House correspondent Jake Traylor tweeting, “After a dark-colored bruise was spotted on Trump’s left hand last week, the President keeps his left glove on during a restaurant stop in Iowa.” Almost immediately, the White House’s “Rapid Response 47” fired back: “FAKE Traylor strikes again. What Fake doesn’t mention is that @POTUS took his glove off to sign hats for some great Iowa Patriots, which he was doing just moments before this screenshot was taken. The pen is literally still in his hand.” This wasn’t quite the own of Traylor that the White House thought, though. The video showed that while there was no glove on Trump’s right hand, he still was wearing a glove on his left hand—just as Traylor reported.