You’re likely to hear a lot this week about whether some government agencies, notably the Homeland Security Department, will run out of money Friday night.

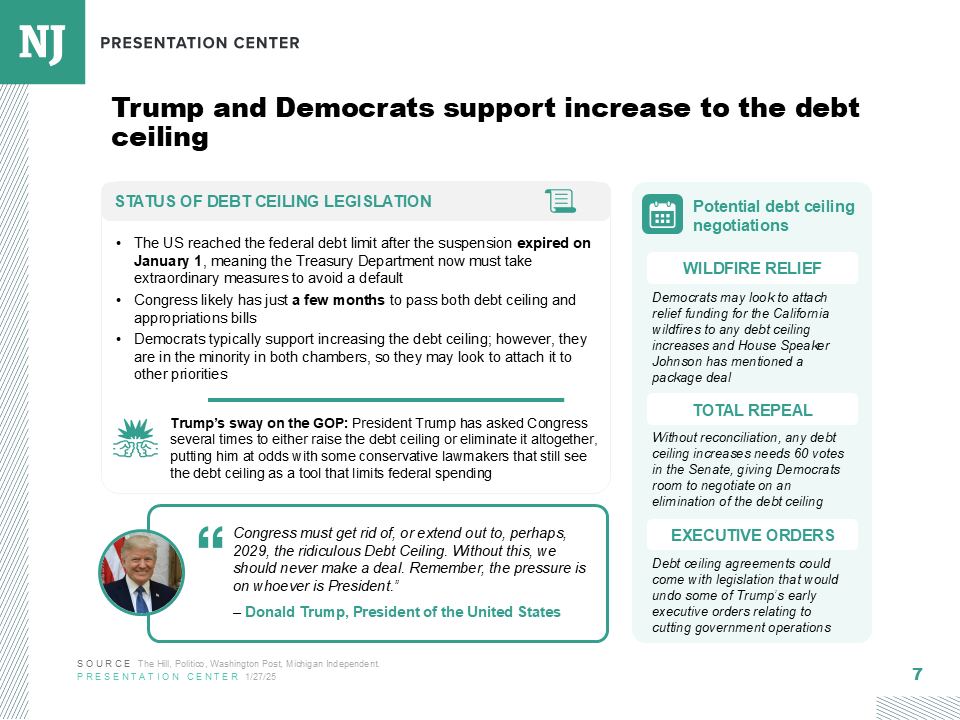

What you probably won’t hear is what all this means to a potential fiscal crisis growing every day: the ever-growing federal debt.

The political spotlight this week will involve the furor over DHS, sparked most recently by the killing on Saturday of ICU nurse Alex Pretti by federal border patrol agents in Minneapolis. Democratic outrage over the incident, as well as lawmakers’ anger toward Trump administration immigration policy in general, could make it tough to pass spending legislation before Friday.

But even before the Saturday shooting, the legislative focus has been largely on policy, not numbers.

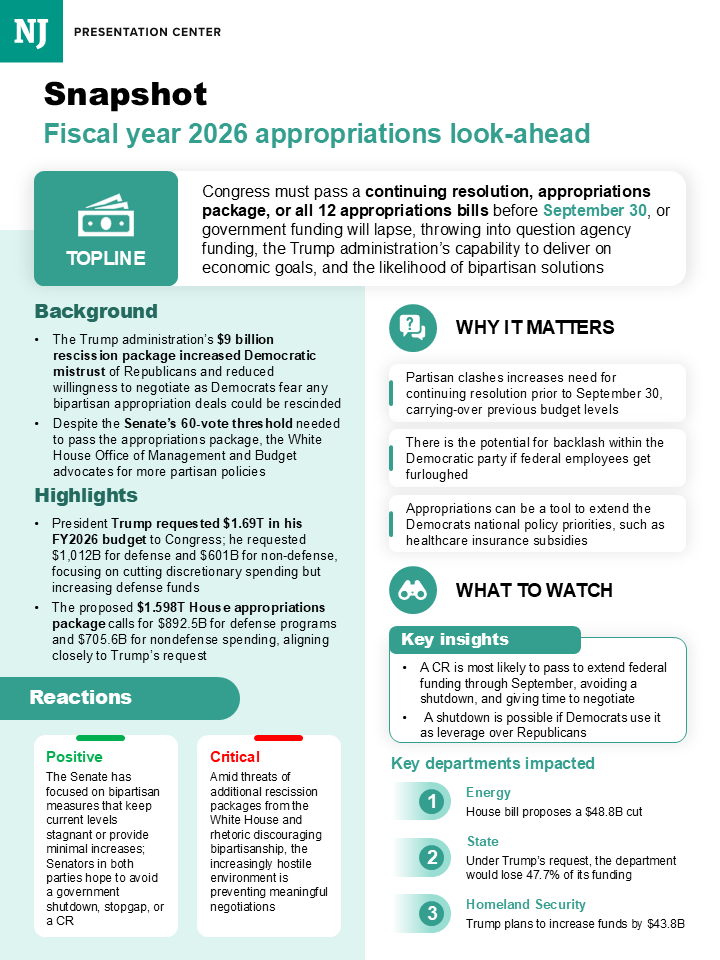

The numbers are relentlessly grim. The federal budget deficit hit $1.8 trillion in fiscal 2025, the 12-month period that ended Sept. 30. Though that was down slightly from the previous year, deficits have been near or above $1 trillion each fiscal year since 2019.

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office projects it will hit $1.7 trillion this fiscal year. In the first three months of fiscal 2026, the deficit was $601 billion. CBO estimates that net interest payments on the national debt should hit $1 trillion this year.

Without significant steps to trim spending or raise taxes, CBO sees the deficit rising to $2.7 trillion by fiscal 2035. That would be 6.1 percent of gross domestic product, the value of the nation’s goods and services. Over the last 50 years, the deficit’s percentage of GDP has averaged 3.8 percent.

So where is the outrage?

It’s building slowly, said Carolyn Bourdeaux, president and executive director of the nonpartisan Concord Coalition, which works to bring awareness to the budget crisis.

While top policymakers and corporate executives realize the problem, “it will take time to build the awareness and re-engage” the general public, Bourdeaux said. “People don’t understand the nature and scope of the problem.”

So far, any concern about the deficit isn’t being translated into bold action.

“The good news is that there is some attention to the issue broadly. There are various pieces of legislation that wouldn’t fix this issue but at least put a focus on it,” said Marc Goldwein, senior vice president at the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

Congress’ bipartisan Problem Solvers Caucus, for instance, is pushing legislation to create a fiscal commission developing recommendations “to stabilize our country’s finances,” the caucus said. The measure would provide Congress “with clear options” for creating financial stability and require lawmakers to act on the recommendations.

“Denial and pretending there is any one silver bullet can no longer be a policy; we clearly need help in charting a real return to fiscal stability,” said Democratic Rep. Ed Case, caucus vice chairman.

But trying to get consensus on how to spend and tax has proven elusive for generations.

Republicans insist that last year’s One Big Beautiful Bill, which extended 2017 tax cuts and created some new ones, will generate enough economic activity that revenues will go up while necessary spending goes down.

President Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers estimated that OBBB, which makes significant spending cuts, would generate more than $4 trillion in economic activity over 10 years while reducing deficits.

Other economists and tax experts disputed the deficit impact.

“The bill’s policies, macroeconomic effects, and interest costs would increase federal debt by $3 trillion, or 7% of gross domestic product by 2034,” the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center estimated. “Within 25 years, these higher deficits would lead to a decline in GDP."

Another wrinkle: Democrats routinely oppose big cuts in social safety-net programs.

Responsible spending is “more about where you better invest," said Sen. Alex Padilla, a Democratic member of the Budget Committee. "When you’re gutting health care, gutting education, getting the foundation of how to achieve a better life and a better future, that’s not just bad policy, it’s pretty bad economics.”

And so, while spending levels won’t increase significantly in the budget bills Congress will consider this week, there’s little movement towards significantly trimming the deficit.

Gone is the political incentive to do so. It’s a sharp turnaround from the period of the 1980s until roughly the early 2010s, when few politicians wanted to be blamed for deficit spending.

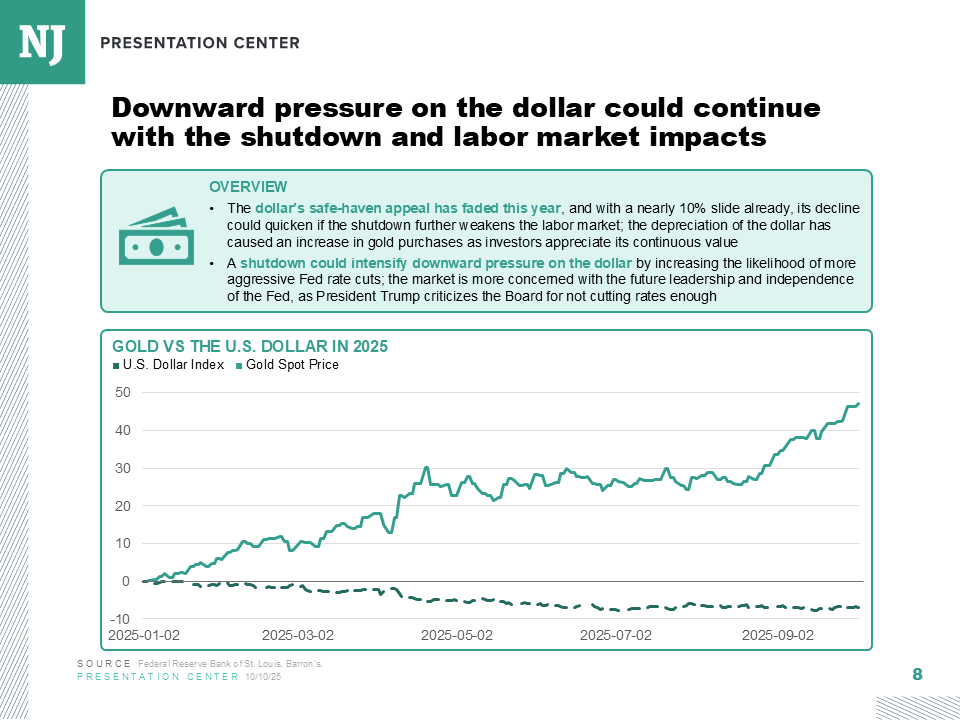

The theory then—and now—is that deficits helped push up interest rates consumers pay. That’s because the government was competing in the marketplace for funds, and competition pushed up rates.

Experts argue that rates do remain artificially high for that reason. They haven’t exploded to 1970s-era double-digit levels largely because of foreign dollars pouring into this country.

Concern remains, though, that this fragile interest-rate environment can’t continue. Mortgage interest rates continue to hover around 6 percent, even though the rate of inflation last year was 2.7 percent and it appears it will maintain that level this year.

The financial markets look ahead, and they see a national debt of $38 trillion and growing. They see Medicare’s hospital insurance-trust fund projected to run out of money by 2033.

In the same year, Social Security’s key trust fund is expected to run out. “At that time, the fund’s reserves will become depleted and continuing program income will be sufficient to pay 77% of total scheduled benefits,” said last year’s Social Security and Medicare trustees’ report.

Goldwein sees 2032 as the year things could get chaotic.

At that time, he said, "interest rates may be high, and you could have Social Security and Medicare running out of money."

"That one-two punch may draw people’s attention.”