Those of us who work in politics don’t always recognize how weird we are compared to the rest of the populace. Even most people who vote regularly are blissfully unaware of a whole lot of the daily political churn in D.C. that we view as critical events. They certainly don’t spend their whole day talking to other junkies about politics.

Maybe they turn on the Today show or Good Morning America but don’t really pay attention because they need to get to work. Maybe they try to watch the evening news, but they’re also managing dinner and kids’ homework. Instead, they pick up information here and there—often on social media. But that’s inconsistent and subject to algorithms that only give them content that they’ll likely engage with. Conversations with friends and family might include some news, but that’s not a complete picture, either.

Meanwhile, for those of us in politics, 2026 came in like a wrecking ball. Not that 2025 was quiet, but when my phone blows up with texts about Venezuela at 5:45 a.m. on the first Saturday of the year, it sets a tone. I know that I’m very weird in my level of attention, as are the people who were texting me. Normal people don’t live like this.

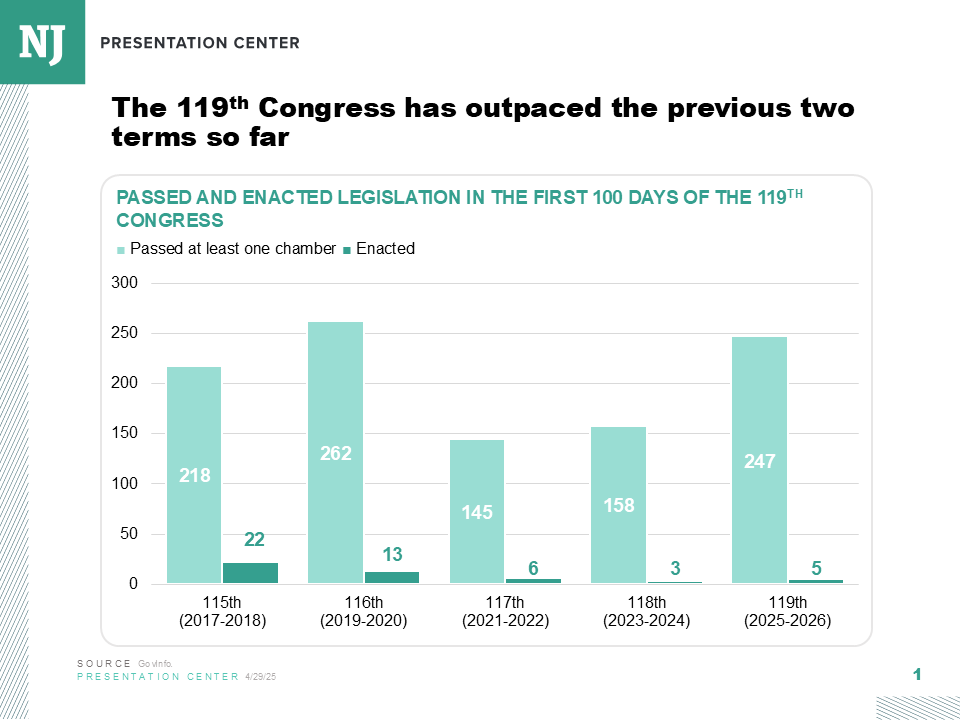

President Trump’s first term in office was a busy, sometimes chaotic information environment. A year into his second term, he is outdoing himself. The administration takes newsworthy action on a dozen different situations every day, and Trump adds to the fray with his constant social media posts demanding takeovers of Greenland and Canada and upending the global order, when he isn’t antagonizing political opponents domestically.

How are normal people supposed to keep up?

They don’t. There’s no way for them to. Those of us who do this for a living can’t keep up. We have to pay close attention in the areas most important to our jobs and let the rest go.

Keep this in mind every time you see polling on an issue, particularly if something major has just taken place. Polling is fairly nimble these days, and we can get a measure of what people think about the U.S. capturing Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela, or Immigration and Customs Enforcement shooting a woman in Minnesota, within a couple of days. But the people answering may or may not really know what has happened. A lot of the time, they’re just answering because they were asked.

Before asking for opinions about an issue, pollsters need to ask how much people know about it. An Ipsos-Reuters poll reported that 42 percent of Americans had heard a lot about Maduro and Venezuela. Awareness of the Minnesota ICE incident was considerably higher—63 percent in a Yahoo poll said they had heard a lot about it, and in a Quinnipiac poll 82 percent said they had seen video of the shooting.

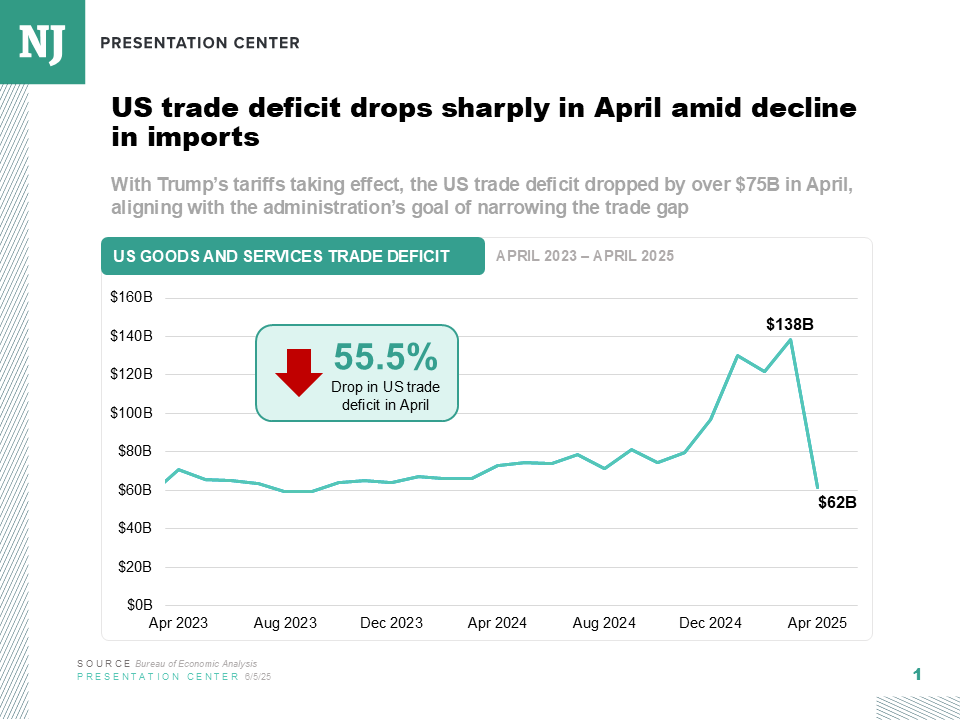

At the end of 2025, the Marquette University Law School poll reported on attention to issues they had polled throughout the year. Would you believe fewer than 30 percent had heard a lot about the New Jersey and Virginia elections in a poll taken the week of those elections? Fewer than 50 percent had heard a lot about the possible release of the Epstein files in September, as Congress argued over it. The top two issues that people had heard a lot about? Tariffs and deportations.

A lot of the time, people give overestimates of their attention levels. A poll question can make it seem like respondents should be paying attention, so seeing one or two social media posts can easily become “heard a lot.” That also applies to what they think about the event, plus there usually isn’t a clear opportunity to say they don’t know. Pollsters don’t want respondents to say “don’t know” as a cop-out, so they don’t give the option. The downside is that people who really don’t have opinions will make one up.

These complexities make polling on issues difficult. We need people to be aware of what’s happening in order to ask about it, and sometimes there isn’t enough time in a survey to ask how much respondents know about every event. We do know that the closer to home the issue is, the more extreme it is, and the longer it stays on the news, the more likely it is to get people’s attention. Most foreign affairs events don’t make the cut. Ongoing tariffs and deportations get more attention.

In a Trump administration that regularly floods us with too much activity, and with a polling industry that polls about everything, be judicious in how you interpret numbers that claim to show a definitive answer to what people think. Those may not be concrete opinions.

Contributing editor Natalie Jackson is a vice president at GQR Research.